Clarifying context in GCSE and A Level English Literature

08 January 2020

In conversations I’ve had with teachers over the last few months, as well as my own experience in the classroom, it’s become clear that as with subject terminology there is anxiety about what context means and how this might look in a response. In this blog, I’m talking about what changed, what we’re looking for, and what advice you can give to move your students forward.

How has ‘context’ changed?

With the move to the reformed qualifications in 2015, there have been some small but important alterations in the place of context. At GCSE level, we deliberately broadened what constitutes ‘context’ particularly at GCSE. While the wording at A Level has not changed, what has is the weighting it has within certain sections of the components.

What kinds of context are we looking for?

Students should consider context a deck of cards with four main suits: social, historical, literary and biographical.

Context is best used to drive student argument about a text, rather than bolted on to demonstrate knowledge. I should note here that if AO3 is awarded 50% of the marks on a question, it doesn’t mean it needs to be 50% of the response – examiners are asked to judge the quality, not quantity of these references.

Social context

Students might feel that social context is obvious but, often these ideas underpin texts and can drive analytical argument.

For example: Lord Capulet’s treatment of Juliet in Act 3, Scene 5 is a betrayal because it both inverts his protection of her at the start of the play and undercuts our social conception of what a good father is. (Exploring how this may have changed over time can be a way to tie the social and historical together.)

In the 2019 examiners’ report for GCSE English Literature, the commentary on the Never Let Me Go question reflects this:

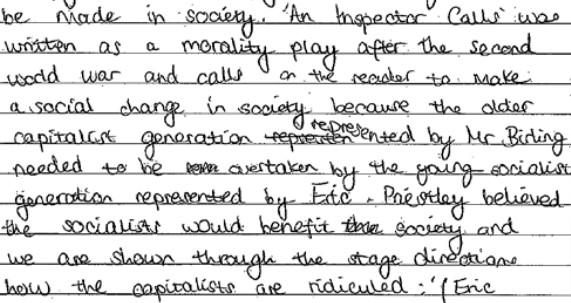

For example, in this 19 mark GCSE answer from 2018 on An Inspector Calls, the student comments on social ideas of generational difference and resentment:

Historical context

Students often reach for historical context as it seems the most discrete and straightforward type of information to learn. What is most useful to them as English students isn’t just knowledge of ‘what happened when’ but considering what the influence those events might have on a text.

Rather than relying on a timeline of events, or flattening original readers and audiences, students should be led by the text: what, or who is this responding to? Exposing students to a range of contemporaneous attitudes can better situate a text appropriately within its time period and political moment.

Literary context

Literary context is one of the best ways to explore contemporaneous attitudes. Exposing students to other work written at the time can demonstrate how the past, and its people, were just as nuanced and complex as we are now.

Situating a text within its contemporaries can also help students see how styles and approaches change in literature, building a better understanding of genre and form.

Likewise, encouraging students to see how a text has not just been influenced by, but has influenced other texts can create a broader understanding of how literature in all its tropes and forms has developed.

For example, in this opening statement from a 2018 A Level Literature paper on ‘The Immigrant Experience’, a student uses their literary understanding as to the basis for their thesis statement at the start of their essay:

Biographical context

Biographical context is valuable but can often, like broader historical knowledge, be reductive. Students need to move beyond a potted biography of an author’s life or mistaking all their work as confessional (we find female writers tend to suffer especially from this approach).

One way to do this is to encourage students to consider how the author’s work might reflect (literally or figuratively) their or their family’s life experiences. Crucially, this should be used to shape an argument, as seen from this 2018 exemplar for A Level English Literature.

Here, biographical context is used to suggest authorial attitude to the stem of the question, in order to demonstrate the direction of the essay:

What might this look like in practice?

In that same An Inspector Calls essay from our 2018 Candidate Exemplars, the student has melded literary (morality play), historical (situating the text as written in reaction to WW2), political (understanding the political and moral struggle at the heart of the play between capitalist and socialist conceptions of society) and biographical context (Priestley’s beliefs).

While not as sophisticated as at A Level, this does demonstrate a GCSE student who uses their contextual information to make an argument about the text – namely that it is calling on “the reader to make a social change”.

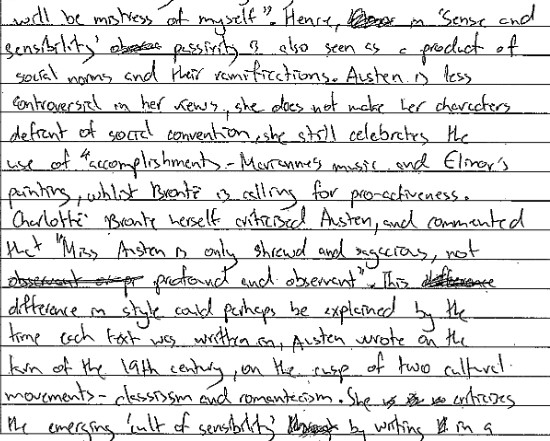

At A Level we see a similar approach in this 2019 exemplar for Women in Literature. Here, the student covers social (women as passive), literary (both Brontë’s views on Austen and the cultural movements of classicism and romanticism) and historical context (situates Austen in her time):

What strategies might help?

I hope this has helped clarify what we mean by context and its place in student responses. I’ll end on three final strategies that might help students problematise both the past and their ideas of context.

- Starting with concepts: the themes or concepts of a text often rely on social contextual understanding. Mapping these concepts with a class help indicate knowledge students are already bringing, as well as finding natural places to build up with literary, historical or biographical detail.

- Reflection, response or resistance: Provide a range of relevant historical and political events that relate to the themes of the text. Students must decide which events are being reflected, responded to or resisted in their text. This prompts students to interrogate this historical knowledge, rather than see it as causation.

- Wider reading: although at A Level, independent wider reading of whole texts is to be encouraged, using a range of small extracts from other texts written at the time, or within the genre, can help students draw connections or contrasts to their studied text (reflecting the Modern Text element of our GCSE English Literature exam).

Stay connected

If you have any questions you can submit your comments below or email us at english@ocr.org.uk. You can also sign up to receive email updates or follow us on Twitter at @OCR_English.

About the author

Isobel Woodger, OCR English Subject Advisor

Isobel joined OCR as a member of the English subject team, with particular responsibility for A and AS Level English Literature and A and AS Level English Language and Literature (EMC).

Isobel joined OCR as a member of the English subject team, with particular responsibility for A and AS Level English Literature and A and AS Level English Language and Literature (EMC).

She previously worked as a classroom teacher in a co-educational state secondary school, with three years as second-in-charge in English with responsibility for Key Stage 5. In addition to teaching all age groups from Key Stage 3 to 5, Isobel worked with the University of Cambridge’s Faculty of Education as a mentor to PGCE trainees. Prior to this, she studied for an MA in film, television and screen media with Birkbeck College, University of London while working as a learning support assistant at a large state comprehensive school.